Rapid Tap was my first attempt at releasing my own Unity game onto various popular platforms and learning about that whole process. It was first released on January 22nd, 2018 on Steam.

Rapid Tap was my first attempt at releasing my own Unity game onto various popular platforms and learning about that whole process. It was first released on January 22nd, 2018 on Steam.

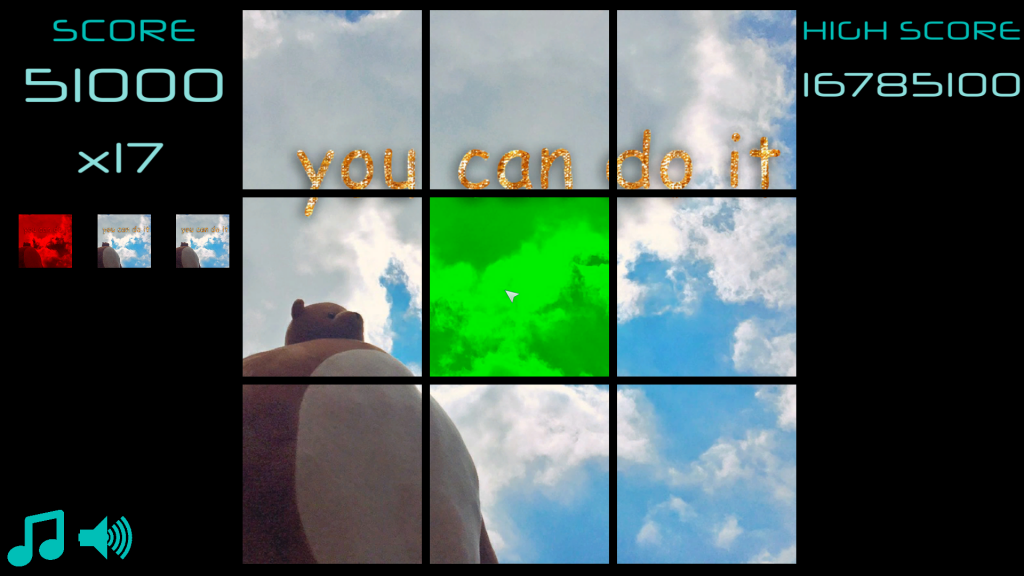

The gameplay itself is very simplistic: a grid of nine squares light up and the player must press them before they go away. They rack up as many correct clicks as they can with three lives. It’s sort of like wack-a-mole, but with funny skins you can play it with. The point of the project was to focus more on learning the process behind how to release a Unity game onto Steam, Android, and iOS for free.

At the time of the project’s start, I had just finished my last exam for my computer science degree in college. Excited for the future and wanting to break into game development, I started a twelve-hour livestream on Twitch where I worked on a game project myself with audience suggestions here and there.

The result was Rapid Tap, whose initial conception was to be a much more simplified version of my Beat Grid project at the time. Since Beat Grid required a MIDI launchpad to play it, it would be difficult to receive feedback on how the gameplay would feel. An easier version that could also be played on their phone seemed ideal, so I worked on the project based off of that.

The only other difference between the two games is that Beat Grid is rhythm-based, while this game isn’t. I learned that having music play during this kind of flashing gameplay confused people into thinking it was a rhythm game though, and they naturally got frustrated. I believe it’s the combination of the gameplay with the music for the game that I choose was what gave off that impression, and I’ll definitely have to keep that in mind for future projects.

Rapid Tap also came at around the time when Steam Greenlight was shutting down and being replaced with Steam Direct. This meant that now you no longer needed to wait for community approval before publishing games onto Steam. To me, it was a great opportunity to learn about the Steamworks SDK and the whole Steam release process.

And of course I wanted to get experience releasing Android and iOS versions of the game as well. The Android version was easy enough to implement, since Google Play only requires a one-time fee and then you’re good to go. The iOS version, on the other hand, was a much more difficult problem. To release a game onto the App Store for iOS you need to pay an annual subscription, own a Mac and an iOS device, suffer through XCode headaches, and deal with Apple’s weird approval process. And apparently soon you can’t even log into your Apple Developer account without a Mac.

All of this was very painful to deal with for me since I didn’t have any Apple products and didn’t want to pay thousands of dollars just to publish a free app to learn. Nevertheless, I did everything I could and worked with my friend who owns Apple devices to get the game released on there for a year. Although now I just don’t want to deal with all the problems related with Apple, so on August 2019 the game will be removed from the App Store.

There were quite a few features with this game that I hadn’t had experience with going into this project that I tried out. In-game advertisements, leaderboards, cheat detection, multiplayer, and skins. Some were more trickier than others, of course.

In-game ads were actually much easier to integrate into the mobile versions of the game than I thought. I always knew the game would be free but I thought it wouldn’t hurt to experiment with ads in the mobile version for awhile. Unity makes it incredibly easy to put ads in, but I programmed in a gameplay timer so that it wouldn’t spam ads at them every time they died. Instead it would only show an ad after more than five minutes of active gameplay (after they died). Since most of the game’s playerbase was all on Steam instead, it never generated much for money. Not that I expected any, really. So I removed ads from them soon after.

The leaderboards were a huge step into implementing the Steamworks SDK and Google Play leaderboards. I know that for most players just having some kind of leaderboard or ranking system can get people hooked, but it wasn’t as easy to implement as I thought. The original scoring system especially caused problems with it. Before, each correct press would give the player 100 points times their current combo. Which lead to huge numbers, with some players even managing to overflow their score and go into the negatives. Fixing that issue with the old scoring system just wasn’t possible due to the Steamwork SDK limitations, so I implemented a simpler system that just scored them based on the number of correct taps. Each tap was one point, the combo didn’t matter. Now the next time I hear about someone overflowing on the game, I can assume they either cheated or they’re some kind of world record seekers.

I found out pretty quickly that where there’s a leaderboard, there’s most definitely cheaters. Especially when your game is free. So I attempted to implement features to prevent some very common forms of cheating, such as using Cheat Engine or spamming clicks. Of course I knew there’d be some people that would eventually program a bot that would just detect when a block flashed green and have it automatically click the circle. There’s not much I can do about that except monitor the leaderboards for very obvious cheaters.

It was very difficult to learn how to program multiplayer, even given how simplistic this game is. I had lots of help and feedback from Twitch viewers and beta testers which helped highlight tons of problems and changes that needed to be made. And thanks to my use of the Photon Engine, it was easy to make the game cross-platform as well. Multiplayer mode has a room/lobby system, a player chat, host options, and a last-man-standing system for the game itself. Whoever lasted the longest would be the winner.

Since I made this game during a livestream and wanted to get people involved with the fun of this project, I went to Twitter and asked everyone to submit random images for skin ideas for the game. The skin would become the nine different buttons that you play the game with. Not a huge thing to implement, only tricky thing about it was designing it to take into account the spaces between the blocks so that the image doesn’t look weirdly spaced out.

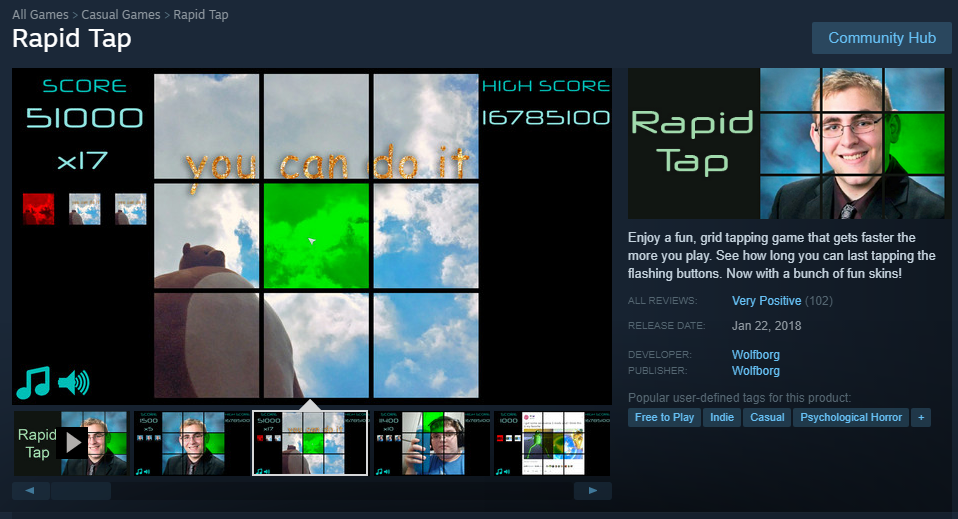

It was all the direct input from the players and the different unique memes they sent to contribute that really helped this project become way more known than I could have ever expected. They even wanted my highschool yearbook photo to be the cover art of the game. I sometimes worry that my face being there will immediately make me never seen as a “real” game developer to some people, but they don’t see the bigger picture. Rapid Tap is more than just a joke game, it’s a game that a small community helped make together with a new developer that wants to learn and grow. Even if it makes for awkward interviews, I’m proud of Rapid Tap, my first officially released project.

Steam: https://store.steampowered.com/app/746920/Rapid_Tap/

Google Play: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.Wolfborg.RapidTap&hl=en_US